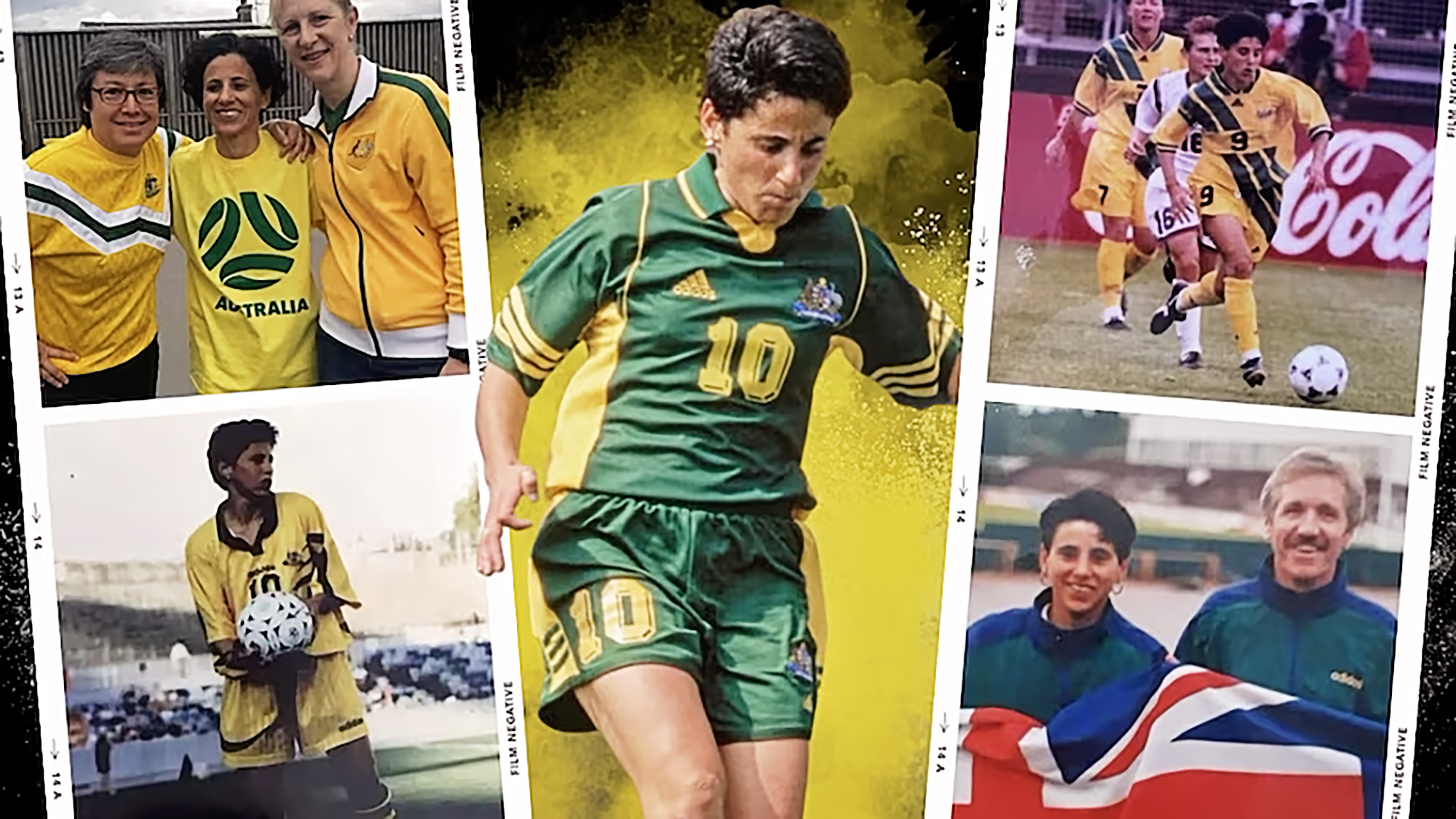

Meet Angela the first Australian to score at a World Cup game.

23 JULY 2023

ANGELA IANNOTTA – FORMER AUSC PLAYER

History happened in a blur.

On June 8, 1995, about 25 minutes into Australia’s second World Cup group match against China, Anissa Tan took a touch near the half-way line and launched the ball upfield.

The speed and distance on the kick was unexpected; the white rubber disappeared into the overcast Swedish sky. China’s central defender, Zhou Yang, was forced to scuttle backwards: her eyes were turned up into the grey clouds, fixed on where she thought the ball was falling.

This is where the details start to fade; the hard outlines dissolving with time and age.

A soccer player wearing yellow holds a ball in her hands during a game

It’s been 28 years since Angela Iannotta made Australian football history. But hardly anybody knows about it.(Supplied: Angela Iannotta)

As the ball dropped towards them, Sunni Hughes — Australia’s centre-forward — ghosted out from behind a nearby Chinese midfielder and took a pressing step towards Yang.

The defender was already swinging her leg at the ball by the time she saw the yellow wall of Hughes’ jersey; her focus ripped in two. She didn’t have time to change direction, to stop or alter the momentum of her kick, before the Australian was right there in front of her.

A squeal pierced the air inside the Arosvallen stadium.

Then, suddenly, the ball was at Angela Iannotta’s feet.

How did it get there? Was it a poor clearance from Yang? A panicked back-pass? Did it rattle off Hughes and spin right into her path?

Iannotta doesn’t remember; the seconds are smeared together now.

But in the moment, she didn’t care. She just did what her father always told her to do, booming in thick Italian from the sidelines of her childhood: dribble and score.

“I just thumped it,” Iannotta says.

“A power shot. In the top corner.

“When I scored it, I was really, really happy because it made it 1-1 against China. And back then, China was one of the top teams in the world: one of the strongest teams to beat.

“It was a pretty good goal, I must say … and then I was really excited and ran towards the bench. Coming from the bench, I wanted to celebrate with the players on the bench.

“I didn’t even realise that was the first goal at a Women’s World Cup. I only realised after two years, reading an article about it. So I scored this goal not even realising it was the famous goal, as everyone says; it’s in the history.

“But I didn’t remember that at all.”

There are not many people who do. Especially not these days.

And why would they, when there’s hardly any evidence that it happened?

In the process of putting this story together, ABC Sport spent several weeks trawling through search engines, public archives, and old websites, trying to track down footage of Australia’s first ever World Cup goal.

In this day of social media and live-streaming and the endless churn of sports content, it’s hard to imagine that a goal as iconic as this would simply fade away, placed in a figurative box on a figurative shelf and left to gather dust.

But aside from a handful of home videos recorded by families at the time, the only proof of this pivotal moment in Australian football history is buried on a database at FIFA headquarters, difficult to locate even through the governing body’s own online archive tool, and costing an unfathomable amount of money to officially license in order to bring it out into the public.

Not even Iannotta herself has a copy anymore; the person whose moment this was. The woman whose name should sit alongside fellow greats like Mark Viduka, Tim Cahill, and Sam Kerr. The player whose entire career was a battle against being forgotten.

“I had a VHS casette of the goal, but I can’t find that anymore,” she says.

“I don’t know where it’s gone.

“I did remember having that goal somewhere, but it’s disappeared now. Back in those years, we didn’t have all the publicity as what they have today. I actually wrote to a journalist in America, but he couldn’t find it for me either.

“That was women’s football back then, you know? It’s not like today.

“Things have changed, and I’m happy things have changed. I’m glad the girls are where they are now and they’ve got all the support they have, because it was hard back then — for all of us.”

History and memory

Who does the history of women’s football belong to? How is its memory kept alive?

Who gets to decide what is remembered, what is celebrated, what is passed down like a family heirloom from one generation to the next?

And who gets to decide what slips away, flickering in and out of the memories of those who were there, cherished only in the minds of the people who lived it — and buried with them, too?

Who are we, and what is this sport, if not the culmination of all of that: a dazzling patchwork of our memories, pieced together like a window of coloured glass?

Iannotta’s mind, like the minds of so many pioneers in women’s football, is like a museum.

We spend three hours speaking one Friday in May — her in Italy, me in Australia — as she walked me through her life and career: pointing at display-cases full of cherished memories, telling anecdotes and stories and jokes and secrets, connecting people and pieces of information in unexpected but revealing ways.

She talks about growing up in Victoria, travelling around Myrtleford and Melbourne and Whitfield in the north-east. Her parents were tobacco farmers who migrated to Australia in the 1960s, and she and her older brothers spent the first few years of their lives moving about before finally settling in Albury.

Her father was a hard man, traditional, set in his ways. He loved football — Angela remembers sitting up watching World Cup finals together in the early hours of the morning — but he never encouraged her to play the way he did with her brothers.

It was only when she went to Italy herself, when she was 7-years-old, that she felt something wake up inside her.

“I’ve got family in Tuscany, so we stayed there for a while, and I was in Naples for a couple of months,” she says.

“And all the scugnizzi — the Naples kids — they’d go down to the streets and play in the middle of the road, or wherever they could. So my brothers used to go down, and I’d follow my brothers.

“We’d play for hours and hours with all these kids we didn’t know, just in the middle of the streets.

“That’s where I think my passion came from. Before then, I didn’t ever think about football. I didn’t kick a ball around when I was young back on the farm, not with my brothers, nothing. It was there, on the streets of Naples.”

When she returned to Australia, there was only one thing she wanted to do.

“But my father, being Italian background, didn’t want me to play,” she says.

“I’d sneak down to the under-13s training, and my dad would figure out where I’d gone, come down and pick me up and take me home again.

“I’d sneak down to training again, he’d come and get me and take me home again. Again and again. I just wanted to play.”

Instead, it was another paternal figure in her life — Rick Porter, a physical education teacher at Murray High School — who opened the door for her. He allowed her to trial for the girls’ team, even though she was just 13-years-old, but saw Iannotta’s raw talent and speed, which she developed running laps around the farm.

“Then one afternoon, he knocked on my door and spoke to my dad,” she says.

“Finally, my dad said:’ yeah, OK, I’ll let her play’. I was the happiest little girl in the world.

“Rick Porter and Ethel Wilson, always knocking on my door, telling my parents that I needed to go and play in Canberra and Sydney. I have to thank those people because they made my dream be possible.”

Her dad remained reluctant, though. He only came to a few games in the years she played in Albury, and only a few more after she’d earned her first cap for Australia at 18.

“He’d stand there on the sideline and yell, ‘you get the ball and just dribble everyone and score!'” she says.

“I always remember those words from my dad and it makes me laugh. He’d say it in Italian, too, so nobody else knew what he was saying.

“But he never really showed that he was happy about this thing, me playing football. In front of his friends, he’d say ‘oh, Angela, she plays for the Matildas!’ and he’d be really proud with his friends, talking about my career.

“But he’d never show me.”

Small acts of disappearance

Decades on, Iannotta thinks her dad’s apathy is partly what drove her away from Australia altogether.

When she was 21, she accompanied her brother on what was supposed to be a two-month holiday back to Italy to visit family.

It was midway through 1992. Australia had missed out on qualifying for the previous year’s inaugural Women’s World Cup by a single goal, and Iannotta — entering into her prime years — began to feel the world opening up ahead of her.

Two soccer players, one wearing yellow and green and the other wearing black and white, stand on the pitch during a game

Angela Iannotta (centre) playing for Australia in a Women’s World Cup qualifying match against New Zealand.(Supplied.)

“I saved up all my money: I was working in a Caltex petrol station, which was a shit job, and I was studying and playing as well, so it was hard,” she says.

“We flew over to Italy in June. We were only meant to be there for a few weeks, but I ended up staying there. I didn’t come back to Australia.”

It was a chance conversation with her uncle that decided it. She’d been playing for the Matildas for a few years by then, but felt she was hitting a ceiling. She needed a new challenge, something to push her beyond herself.

“I knew I was really fast, but I realised something was lacking physically; I didn’t have the fitness, I couldn’t last 90 minutes at that level,” she says.

“I needed training, a proper fitness program, and more games. I needed something to get stronger.

“A week later, my uncle rings me up and tells me he’s organised a try-out with a women’s team near home. I asked, ‘for who?’ and he said ‘Agliana women’s team: they’ve just got promoted into Serie A, the first division. Do you want to trial?’

“I went to Italy on holiday. I didn’t have anything. I didn’t have running shoes, I didn’t have soccer boots, I didn’t even have winter clothes. I had a couple of swimmers, a couple of shorts, t-shirts, a pair of shoes. That was it: a backpack with summer clothes.

“And I said ‘yeah!'”

She doesn’t remember whether she bought a pair of boots to trial in, or if she borrowed them from a cousin, but Iannotta showed up and tried out for Agliana, and a few days later the club called her grandmother’s house (where she was staying) to offer her a contract.

“I don’t know how I did it,” she laughs now.

“I never went back to Australia. I quit my job over there, rang my parents and said, ‘I’m not coming home!'”

Iannotta was just the third Matildas player ever to play their club football overseas, following in the footsteps of Alison Forman and Julie Murray.

And while her first season with Agliana was difficult, the team gradually improved as the years rolled on. She did, too, becoming faster, leaner, able to last longer. Exactly what she needed.

The quality of the players around her helped in that regard. Iannotta absorbed lessons about the game from Italian legends like Carolina Morace, Elisabetta Bavagnoli, and Milena Bertolini: women who went on to coach powerhouse clubs like Juventus, Roma, Napoli, and even the Italian national team.

Iannotta reached her prime two years later, reaching the Coppa Italia final twice in a row while also winning Agliana’s first ever Serie A title in 1994/95.

But despite all that — despite being one of the most successful Australian woman footballers in Europe — Iannotta dropped off the Matildas’ radar entirely.

“Back then, in my first years in Italy, it made it really hard with the national team,” she says.

“Every girl’s dream was to play for the Matildas. Back in Australia, the highest grade was the national team because we didn’t have a national league, really. So you wanted to play for the Matildas.

“But being in Italy made it really hard for me because it seemed like they didn’t know who I was. After [head coach] Steve Darby moved on, there was another coach that they brought in, and they forgot about me.

“I remember reading a newspaper article here that the Matildas had qualified for the 1995 World Cup, and I said, ‘oh god! I didn’t know about this!?’

“They completely forgot about me after the 1991 World Cup. Then in 1992, when I went to Italy, people just lost trace of me. No one ever got in contact with me … I was just sort of got lost playing in my league.

“So I reached out to them [and said]: ‘Hey! Look! I’m still around! Even though I’m playing in Italy, I’m still here, my dream is still to play for the Matildas.'”

It was Tom Sermanni who finally brought Iannotta back into the fold, flying her from Italy to Canberra to play a series of friendlies against New Zealand as he whittled down his 1995 World Cup squad.

She was elated. Validated. And, after all this time, seen.

But it was one close call after another when it came to Iannotta’s elusive World Cup dreams. Six months before the tournament in Sweden, the forward suffered an injury that still, to this day, she hasn’t told many people in Australia about.

“I broke my shoulder,” she says, a little sheepishly.

“Carolina Morace got a two-game suspension for some reason; I’d been on the bench a lot, so finally it was my turn to start [for Agliana].

“We played Milano, and I think the game had just kicked off — 10, 15 seconds in — and I got knocked over and broke my collarbone. That was in November of 1994.

“I had an operation, got back to playing in January, was feeling really good. But there was something not quite right with my shoulder.

“I’d had two wires put in, and one of them had started poking out against my skin. It was a nightmare. It was a disaster. It was really giving me troubles. I was supposed to get them out after three months, but because of training and other commitments, I couldn’t get them taken out by the surgeon.

“Then at the World Cup, there were certain movements I did where the wires would poke out, so I’d go ‘oh my god’ and had to do these funny things to my shoulder to push them back in.”

Not that you’d know it from the way she played.

Iannotta was one of the stand-outs for Australia in Sweden. The work she’d done in Italy over the years to develop her game culminated in a dazzling individual tournament, her scything movements and rapid pace often praised by commentators and journalists alike.

She came off the bench in the opening group-stage clash against Denmark, and despite losing 5-0, she’d impressed Sermanni enough to warrant a start in the next game against heavyweights China, who would finish fourth before reaching the final in 1999.

And that was where it happened. The history that hardly anybody has seen.

In late May, ABC managed to find footage of Iannotta’s iconic goal.

She hadn’t watched it in over two decades, convinced it had been lost to time.

And while license restrictions mean we cannot show it to you, we were able to show it to Iannotta and capture her reaction to watching the goal that made her one of Australia’s most important footballers.

Fading from view

The following year was the beginning of the end of Iannotta’s national team career.

Ahead of the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, the newly-nicknamed Matildas flew to Seattle to take part in a training camp and a pair of friendlies against world champions in waiting, the USA.

It was two weeks before Iannotta was due to fly to Japan, where she’d signed a lucrative $50,000-per-season contract with top-flight club Panasonic Osaka alongside Australians Sunni Hughes and Cheryl Salisbury.

But during a Matildas training session, a teammate awkwardly tumbled into Iannotta’s lower leg, twisting her knee and ankle. Hospital scans confirmed the worst: she’d broken her right fibula and would be out of action for months.

She flew straight home to Albury. Her experience with her shoulder had caused her such anxiety that she opted against surgery, instead electing for a plaster cast to let her leg heal naturally.

But it never really did. She played a handful of games for Osaka, including one where she scored a goal against the backdrop of a cloud-haloed Mount Fuji, before heading back to Italy on holiday to visit her old Agliana teammates.

It was there, during a kick-around training session, that her foot planted oddly in the grass and she heard another loud crack.

Same leg. Same break. All over again.

She stayed in Italy this time, rehabbing her leg properly, before trying to work her way back up to fitness and find another club to play for. The Matildas, as she expected, were nowhere to be seen.

“When you’re overseas, they don’t know who you are,” she says.

“They don’t know anything about what you’re doing. Those were the times back then; it was the 90s.

“So I remember they had World Cup qualifiers, and I get on the phone and say again, ‘hey, look, I’m still around, are you still interested?’

“My aim was to play in the Olympic Games, because we had the 2000 Sydney Olympics coming up after the World Cup in 1999. I wanted to play in both.”

She was scouted by new head coach Greg Brown, who’d been in Europe to watch opposition national teams ahead of the ’99 tournament in the USA.

He was impressed enough by Iannotta, who at that point was playing regularly for another club in Serie A, and was offered a contract with the Australian Institute of Sport to begin training for the World Cup.

She hated it. The environment was different to Italy, the training sessions weren’t as rigorous, she didn’t feel as comfortable. She would take herself off to the athletics track and do extra 1km runs and sprints to top up what they were given. They were also paid a pittance, forcing the players to pick up extra jobs to earn some money on the side.

Iannotta became an AIS tour guide and a shuttle-bus driver, and tells stories of driving around iconic athletes like Cathy Freeman, Evonne Goolagong, and several Indigenous AFL and NRL players.

She was eventually chosen for the ’99 tournament, but sat on the bench for most of the games. She knew she wasn’t fit. Her peak had passed, and a new generation was emerging. She began to feel like she was just taking up space.

Her last game for Australia was that same year. Injury, fitness, and coaching disagreements saw her career fizzle out before she’d wanted it to.

“It was hard, those ten years,” she says.

“I hadn’t got many games with the Matildas because of injury and being overseas. I just felt like they forgot about me.

“I wanted so much to play for the Matildas, to play at World Cups, to play at Olympic Games. I didn’t give up. Sometimes I think, ‘if I didn’t play football, maybe I would’ve been better in life’.

“But I’m happy with everything I did with my football career. I represented Australia. I’ve got that famous goal. That’s part of history.

“It was a hard life back then in the 80s and 90s just following your dreams.”

Keeping the past alive

Iannotta is in her 50s now and visits Australia when she can, and spends much of her time watching women’s football in Italy or training for triathlons to stay active and challenge herself.

She keeps tabs on all the Matildas, reading everything she can get her hands on, watching from a distance as the team has progressed from one generation to the next.

She was there in France in 2019 when Italy defeated Australia in the first group game, bumping into old teammates she hadn’t seen in decades, reflecting back on the time she was there, on that pitch, in that jersey, opening the door that so many women after her have walked through.

“I’ve had a lot of people ask me if I’m coming back for the World Cup, and I always jokingly say: ‘oh, no one’s got in contact with me!’ she laughs.

“But I’ll be watching as much as I can. It’s so exciting. I’m happy for the Matildas.

“The women’s game has come such a long way, it’s unbelievable. The women’s Serie A here turned fully professional last year. If they get injured, they get paid. If they’re pregnant, they get paid. They get holiday pay, everything.

“Sometimes I wish I was 20 years younger. But I’m happy with what I’ve done, and it’s great that the game is where it is now because of that.”

As the women’s game grows, so too does our collective responsibility to remember the pioneers who carried it on their shoulders when few others did.

The hunt for footage of Iannotta’s goal is a symptom of a sport that, in Australia, has a tendency to forget itself; to lose sight of its deeper foundations in the shifting sands of the present.

This is a particular struggle in women’s football, where decades of disinterest has meant these origin stories have rarely, if ever, been told.

Instead, they are stored away in the scrapbook memories of those who lived it; the women who were there, throughout it all, creating history in the shadows. We are only as old as we remember.

“It was hard for all of us, not only me, but for everybody,” Iannotta says.

“So much has changed. I went to Rome to watch the Champions League quarter-final against Barcelona, and there was 43,000 people or more in the stands.

“I was with one of my friends, Antonella Carta, who was one of the top footballers here in Italy in the 90s. We were sitting there in the stadium, and I was just thinking, ‘god, look at all these people.’

“I’m happy that women’s football has grown because of us. It’s come a long, long way. Hopefully it gets even better.”

Angela Iannotta scored Australia’s first ever World Cup goal in Sweden in 1995. But she almost didn’t make it there at all. Artwork: by KYLE POLLARD

© The Border Mail

© The Border Mail © The Border Mail

© The Border Mail